Therapy for Bipolar Disorder

While medication is an important part of treating bipolar disorder, a combination of medication and therapy is far more likely to help people prevent relapses and to provide a better life overall. On this page, I will discuss some of the most common forms of therapy, how they work, and how they apply to bipolar disorder specifically.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy or CBT is based on the insight that our ideas, emotions and behavior are mutually reinforcing. In other words, we tend to think and behave certain ways when we feel certain ways, and we tend to feel certain ways when we think and behave certain ways.

Cognitive behavioral therapy has its roots in two movements, cognitive therapy and behavioral therapy. Cognitive therapy was developed by Aaron T. Beck in the 1960s, and focuses on changing our cognitions and thereby our emotions. Behavioral therapy was developed by B.F. Skinner among others in the 1950s, and focuses on changing our behavior and thereby changing our emotions. Both are reactions to the psychoanalysis of Sigmund Freud, and have merged together to form cognitive behavioral therapy.

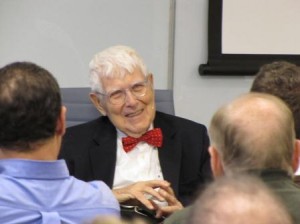

Source: Beck Institute - Fair Use Rationale: to illustrate the person(s), product, event, or subject in question.

There are several common steps involved in cognitive behavioral therapy:

- The patient learns to recognize emotional states, especially focusing on physiological changes that occur during different moods. Only by being able to recognize moods will the latter steps be possible.

- The patient is trained to consider which thoughts accompany which moods. For instance, if the patient is depressed, what thought is it that accompanies that particular bout of depression?

- The patient learns to look especially for strong and recurrent thoughts, sometimes called “hot thoughts”. These will often be as broad as “I’m terrible at everything” or “Everyone dislikes me”.

- Rather than simply bootstrap away these thoughts, the patient looks at evidence on both sides of the thought. What is the evidence that I am terrible at a given task? What is the evidence that I am good at it?

- The patient then tries to develop a balanced thought based on the evidence, such as “People have told me that my work is good and keep hiring me, but I know that I tend to rush things when I am late.”

- The patient then tries out new behaviors based on these balanced thoughts. So, for instance, someone might try offering to do some work in a new area, or to try not to avoid something that normally causes anxiety. These behaviors reinforce both the cognitive and mood changes.

The goal is to use the more balanced thoughts to alter the emotional reactions that people have to things, while at the same time develop new modes of behavior in response to those balanced thoughts. This process can continue indefinitely until the person’s emotions are based on his or her balanced thoughts rather than on his or her hot thoughts or pathologies.

CBT has been shown to be very effective for depression, for anger and for anxiety, including depression, anger and anxiety among people with bipolar disorder. It is less effective, however, at dealing with the euphorias of hypomania and especially mania.

Psychodynamic Therapy

Psychodynamic therapy is a descendent of Freud, but without some of his more controversial claims such as the Oedipus Complex. As opposed to CBT, which focuses on conscious thoughts, psychodynamic therapy seeks to work out conflicts between someone’s unconscious motivations that might either be working against each other or that might be working against one’s conscious motivations.

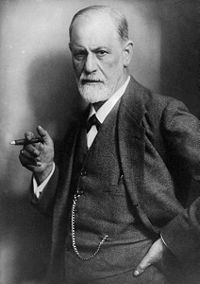

Public Domain

Psychodynamic therapy is a type of talk therapy, except that the patient does almost all of the talking. Because the motivations are unconscious, the belief is that patients, by talking about certain things, will come to be aware of what is actually motivating them. The therapist, on the other hand, mostly asks questions designed to lead the patient to insight about what is actually motivating them.

One of the most common theories in psychodynamics is the belief in what is called transference. In transference, the patient projects some other person onto the person with whom they are dealing and then plays out some sort of previous conflict with that other person. This leads to patterns of behavior that can be self-defeating. One important way in which a patient receives insight is to recognize which conflicts are being played out in which contexts and thereby see through the illusion, preventing the transference.

Unlike CBT, which is a self-help system, psychodynamics cannot really work outside of the context of therapy; it can never become a form of self-help. Some psychodynamic therapy is short-term, but for others it is lifelong. This depends on the therapist, but also the type and number of issues with which the person is dealing.

Psychodynamic therapy can help in the reduction of bipolar symptoms, and also with the improvement of the overall life of the person with bipolar disorder. Nonetheless, like CBT, psychodynamic therapy, no matter how successful, cannot prevent manic episodes on its own, and is almost always used in conjunction with medication.

Interpersonal and Social Rhythm Therapy

Unlike the other forms of therapy discussed above, Interpersonal and Social Rhythm Therapy or IPSRT was designed specifically for use in bipolar disorder. It was developed only within the last ten years and its creators were Ellen Frank and others at the University of Pittsburg. It is a form of talk therapy, but includes the teaching of skills such that the therapy ultimately becomes a form of self-help (although the treatment may continue indefinitely with the therapist monitoring its use).

Source: Dave Stokes - CC BY 2.0

IPSRT is a three-phase treatment process, each of which leads to the point where patients are either able to maintain the rhythms and relationships themselves or at least do so with monthly monitoring:

Phase One: Psychoeducation and the Social Rhythm Metric

The first phase has three goals: for the patient to learn about bipolar disorder, for the therapist to gather a detailed psychiatric history and for the patient to learn to measure his or her social rhythms:

Psychoeducation: The patient learns about bipolar disorder, its symptoms, medications, their side effects and how to look for warning signs of impending episodes. Without this awareness, the patient will not be able to contribute fruitfully in his or her own treatment.

Psychiatric History: Here, the therapist takes a detailed history of past bipolar episodes, looking specifically for triggers that have caused those episodes by the disruption of rhythms and relationships. The goal is to understand what kinds of rhythm and relationship triggers most affect this particular patient.

Social Rhythm Metric: The patient learns to measure his or her patterns during the week. This includes such factors as times going to bed and waking up, eating, first contact with other people, work activities, types of work activities and social activities.

Phase Two: Altering of Rhythms and Relationships

In the second phase, the patient learns to spot those disruptions to rhythms that provide potential triggers and to reshape his or her life such that it has a more predictable schedule with better relationships.

Part of this includes things like developing standard sleeping and waking times, trying to create work schedules that aren’t radically variable and learning to deal with disruptions in rhythm such as loss of a job or integrating themselves into a new community after a move.

In terms of relationships, the therapist and the patient will focus on one or two relationships in an attempt to better handle transitions in those relationships. This can include grief at the loss of a loved one, coming to terms with lost opportunities from mental illness (a kind of relationship with a hypothetical self), transitions such as new relationships or broken relationships, resolving relationships that are either problematic or endangered, or simply developing relationships in the case of people who are isolated.

Phase Three: Maintaining the Progress

In the final phase, treatment is reduced to once a month, as the patient has learned to monitor his or her patterns using the Social Rhythm Metric and to think about how potential changes will affect those rhythms, dealing with those changes appropriately. The monthly maintenance focuses on strategies for dealing with recent, upcoming or potential changes in rhythms or relationships that cannot be prevented. Some patients will choose to work on their own after this, but this phase may continue indefinitely, depending on the needs and desires of the patient.

Conclusion

These are only three of the most common forms of therapy for bipolar disorder, but I hope they give some sense of the type of options available. Whichever form of therapy is chosen, medication with therapy is far more effective at treating bipolar disorder than medication alone, so having a therapist can really benefit anyone with bipolar disorder.

Leave a Reply